Autistic People

Last Modified 22/05/2024 14:10:50

Share this page

Introduction

Autism is a neurodevelopmental condition which is often included in discussions of 'neurodiversity' along with other conditions such as ADHD, dyspraxia, Tourette's syndrome and others. Autism is a distinct 'neurotype' and autistic people will experience issues unique to them.

Autistic people experience patterns of thought, cognitive processing, social issues and behaviour which can include but are not limited to the following factors:

- Difficulties with social skills/understanding social norms and cues

- Fixed patterns of behaviour and routines

- Sensory needs/sensitivities

- Repetitive behaviours known as 'stimming' which can serve a variety of purposes

- Fixed patterns of 'straight-line' or 'bland white' thinking, characterised by having concrete schemas into which the world around them must fit

- Issues around creativity/problem solving/executive function

These features can produce both disabilities and advantages in the context of a world which is designed with people who are not autistic in mind.

As the UK National Autistic Society identifies, the definition of autism is an evolving one:

“The definition of autism has changed over the decades and could change in future years as we understand more. Some people feel the spectrum is too broad, arguing an autistic person with 24/7 support needs cannot be compared with a person who finds supermarket lights too bright. We often find that autistic people and their families with different support needs share many of the same challenges, whether that’s getting enough support from mental health, education and social care services or being misunderstood by people close to them.”1

The estimated prevalence of autistic adults in the UK is 1.1%, or about one in 95 people.2 Some studies estimate that rates among children could be as high as 1.76% (one in 57), and possibly higher taking into consideration the potential under-estimation of those meeting diagnostic criteria.3

Social and medical/diagnostic models of autism

Over the past forty years autistic people have been central to the emergence of different ways of viewing neurological variations and those who have them. The term neurodiversity emerged in the 1990s in recognition that brain function is diverse, and autism and other neurodivergence (e.g. ADHD) are part of a wide-ranging spectrum of neurocognitive functioning. The neurodiversity movement challenges the definition of autism and other neurological conditions that are based on a medical/diagnostic model that assumes a ‘normal’ or healthy brain (from a neurotypical, or NT, perspective). Instead of being a condition or problem to be treated and a justification for stigmatisation and prejudice, neurodiversity is something that should be understood as part of overall human diversity and a source of creativity and social benefit.4,5

Whilst language around, and responses to, autism and autistic people are changing, most autism statistics relate to clinical diagnoses of autism. The World Health Organisation’s diagnostic categorisation system ICD-11 defines autism as a lifelong disorder that has a great impact on the individual and their family or carers. Autism spectrum disorders (ASD) are diagnosed in children, young people, and adults if these behaviours meet criteria defined in DSM-5 and ICD-11 diagnostic systems and have a significant impact on function. Clinical diagnosis tends to be defined by behavioural differences and difficulties with reciprocal social interaction and social communication, combined with restricted interests and rigid and repetitive behaviours.6,7

Autism statistics may not present a full picture of the number and needs of autistic people for a number of reasons, such as:

- Individuals, families or friends may be unaware of autism, or may not see it as being related to them

- Statistics only include those with official diagnoses, and not a wider body of people who may or may not self-identify as part of the autistic community

- Some people may not be willing or able to talk about concerns or seek a diagnosis (and some may be resistant to diagnostic models)

- Professionals or others supporting the person may not pick up on concerns or know how to broach the subject (for example, in relation to women, where there is a recognised gender diagnosis gap)8

- There is wide variation in rates of identification and referral for assessment, waiting times for diagnosis, models of multi-professional working, assessment criteria and diagnostic practice

Whilst treatment for autism is neither possible nor, for many, appropriate, autistic people and their families may benefit from treatment for co-occurring conditions (such as anxiety or depression) and from information, advice, support and advocacy around areas such as self-care, mental wellbeing, independence, employment and training, and navigating services. With such diversity, it is important to ensure provision meets a wide range of needs. Services should also engage autistic people, both individually and collectively, in responding to their needs appropriately and improving the accessibility of provision to neurodiverse people in general.

Facts and figures

The populations of adults predicted to be diagnosed with autism (an autisitic spectrum disorder) in future years are shown in figures 1 and 2. Whilst there is some variation across age groups, the number of people with a diagnosis of autism is expected to grow slightly over the coming decade, with a larger predicted increase between 2030 and 2040. This is almost entirely due to an increase in males with autism, particularly those aged 65 and over. As these tables highlight, autism diagnoses are considerably more common among males than females.

Autism in adults

Figure 1 - males predicted to have diagnosed autism in Blackpool, by age

| Age | 2023 | 2025 | 2030 | 2035 | 2040 |

|---|

| 18-24 |

90 |

90 |

99 |

104 |

97 |

|---|

| 25-34 |

158 |

155 |

146 |

148 |

158 |

|---|

| 35-44 |

140 |

142 |

149 |

146 |

139 |

|---|

| 45-54 |

155 |

148 |

142 |

153 |

158 |

|---|

| 55-64 |

182 |

184 |

169 |

149 |

146 |

|---|

| 65-74 |

133 |

137 |

157 |

166 |

155 |

|---|

| 75 and over |

113 |

119 |

126 |

137 |

157 |

|---|

| Total males |

971 |

975 |

988 |

1003 |

1010 |

|---|

Source: PANSI/POPPI

Figure 2 - females predicted to have diagnosed autism in Blackpool, by age

| Age | 2023 | 2025 | 2030 | 2035 | 2040 |

|---|

| 18-24 |

10 |

10 |

11 |

11 |

11 |

|---|

| 25-34 |

17 |

16 |

15 |

15 |

17 |

|---|

| 35-44 |

16 |

16 |

16 |

16 |

15 |

|---|

| 45-54 |

17 |

17 |

16 |

17 |

17 |

|---|

| 55-64 |

20 |

21 |

19 |

17 |

17 |

|---|

| 65-74 |

15 |

15 |

17 |

19 |

18 |

|---|

| 75 and over |

16 |

17 |

17 |

18 |

20 |

|---|

| Total females |

111 |

112 |

111 |

113 |

115 |

|---|

Source: PANSI/POPPI

Emerson and Baines (2010) estimate that between 20% and 33% of adults with learning disabilities are also autistic.9 Whilst prevalence estimates need to be treated with caution since both learning disability and autism involve 'hidden' or undiagnosed populations, this range would indicate that in 2020, between 515 and 849 adults in Blackpool had both a learning disability and autism.

Autism in children

Emerson and Baines (2010)9 estimate that, in the UK, between 1% and 1.5% of children have an autistic spectrum disorder. Applying these proportions to the mid-2022 under-18 population of Blackpool suggests a lower estimate of 282 and an upper estimate of 423 children with autism in Blackpool. The more recent estimates of 1.76% of children would equate to approximately 458 children in Blackpool.3

Further estimates from Emerson and Baines (2010) suggest between 40% and 67% of autistic children also have a learning disability. This would give a range of between 113 and 284 under-18s in Blackpool who are both autistic and have a learning disability (based on ASD estimates above).

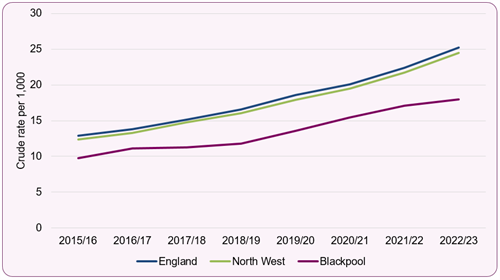

School census data shows in 2022/23, 340 children with diagnosed autism were known to state-funded schools in Blackpool. Of these, 121 were in primary schools, 50 in secondary, and 169 in special schools (with nine attending an alternative provision school). There were 274 with education, health and care plans (EHCP) and 66 in receipt of special educational needs (SEN) support. This continues to increase, though the overall rate of children with autism diagnoses known to schools in Blackpool remains lower than both North West and national rates (figure 3).

Figure 3: autistic children known to schools: Blackpool, North West and England, 2015/16 to 2022/23

Source: Department for Education, Special Educational Needs in England 2022/23

Source: Department for Education, Special Educational Needs in England 2022/23

National and local strategies

-

- The National Strategy For Autistic Children, Young People and Adults: 2021 to 2026 sets out a five-year vision to improve the lives of autistic people, their families and carers, building on the previous strategy and responding to increases in diagnosis and in the reported impact of COVID-19. The strategy sets out six themes:

- improving understanding and acceptance of autism in society

- improving autistic children's and young people's access to education, and supporting positive transitions into adulthood

- supporting more autistic people into employment

- tackling health and care inequalities for autistic people

- building the right support in the community and supporting people in in-patient care

- improving support within the criminal and youth justice systems

The strategy highlights the importance of collaborative working across national and local government, the NHS, the education system, the criminal and youth justice systems, and with autistic people and their families.

Locally, the NHS Primary Mental Health Autism Team works alongside Blackpool Council Adult Social Care Autism Team to provide services to autistic adults in Blackpool. The NHS Primary Mental Health Autism Team undertakes diagnostic assessments for autism and mental health and offers post-diagnostic health support and interventions. The Adult Social Care Autism Team, established in 2019, assess the social care support needs of autistic people (with or without a clinical diagnosis) and offer flexible care plans tailored to the individual. A joint pathway between the two services is currently under development.

The National Autistic Society also facilitates an adult support group for those aged 16+ from the Blackpool area.

[] National Autistic Society. What is Autism. https://www.autism.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/what-is-autism

[] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2020) Autism in adults: How common is it? https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/autism-in-adults/background-information/prevalence/

[] Roman-Urrestarazu, R., van Kessel, R., Allison, C., Matthews, F.E., Brayne, C. & Baron-Cohen, S. (2021) Association of Race/Ethnicity and Social Disadvantage With Autism Prevalence in 7 Million School Children in England. JAMA Pediatrics, 29 March 2021. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.0054

[] Singer, J. (2017) Neurodiversity: The Birth of an Idea. Judy Singer.

[] Also see: Walker, N. / Autistic UK. The Neurodiversity Paradigm. https://autisticuk.org/neurodiversity/

[] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2021) Autism spectrum disorders in adults: diagnosis and management. Update 14 June 2021. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg142

[] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2017) Autism spectrum disorder in under 19s: recognition, referral and diagnosis. Updated 20th December 2017 https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg128

[] see National Autistic Society ‘Diagnosis’ webpages. https://www.autism.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/topics/diagnosis

[] Emerson, E. & Baines, S. (2010) The Estimated Prevalence of Autism among Adults with Learning Disabilities in England. Improving Health and Lives: Learning Disabilities Observatory