Smoking

Last Modified 20/02/2024 09:23:25

Share this page

Introduction

Smoking continues to kill almost 75,000 people in England every year and is the number one cause of preventable death in the country, resulting in more deaths than the next five causes combined (obesity, alcohol, road traffic accidents, drug abuse and HIV infection)1. Tobacco use is also a powerful driver of health inequalities and is perhaps the most significant public health challenge that we face today.

Facts and Figures

Smoking prevalence in Blackpool

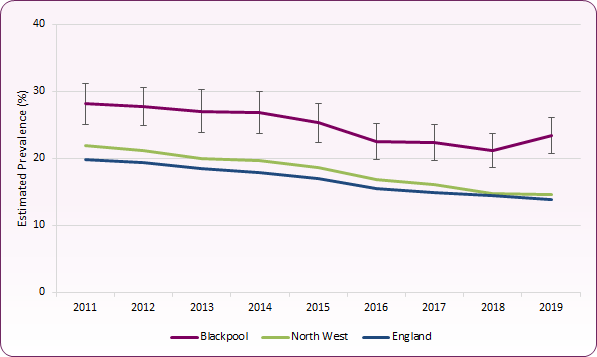

In England there has been steady decline in smoking prevalence in the adult population, with a reduction from 19.8% in 2011 to 13.9% in 2019. The picture in the North West as a whole is similar to England with smoking prevalence showing a similar decline. In Blackpool, there was a decline from 28.1% in 2011 to 21.1% in 2018, however this increased to 23.4% in 2019, as seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Trend in smoking prevalence in adults aged 18+, Blackpool and England

Source: PHE, Local Tobacco Control Profiles for England

Source: PHE, Local Tobacco Control Profiles for England

For COVID-19 affected 2020, one of the main sources of smoking prevalence estimates, the Annual Population Survey (APS), shifted to telephone only. Estimates were affected by this methodological change, with a "sudden and implausible drop" in the proportion of adults across the country who reported smoking2. As a consequence, 2020 prevalence figures are lower than would have been expected if data collection methods had stayed the same, and cannot be compared to previous years. The 2020 prevalence estimate for Blackpool was calculated to be 19.8%, with an estimate for England of 12.1%.

Smoking prevalence and deprivation

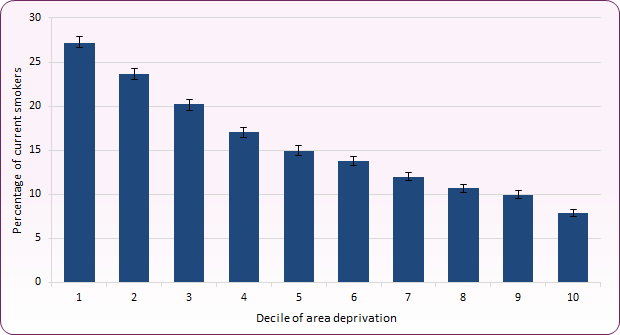

Many of the local authorities with the highest proportions of smokers rank among the most deprived in England. In 2016, people living in the most deprived areas of England were four times more likely to smoke than those living in the least deprived areas. This is reflected in the outcomes for diseases such as lung cancer and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) where smoking is the biggest risk factor. Deaths from respiratory diseases are more than twice as common in the most deprived places in England as in the least deprived places3.

Figure 2 shows smoking prevalence in England by deprivation index, where decile 1 represents the most deprived 10% of areas and decile 10 represents the least deprived, indicating that the higher up the Indices of Multiple Deprivation scale, the higher the estimated smoking prevalence.

Helping disadvantaged smokers quit, and stopping those in deprived communities from starting smoking are the best ways to reduce health inequalities.

Figure 2: Smoking prevalence by deprivation indices: England, 2016

Source: Office for National Statistics (ONS) (2018), Smoking Inequalities in England, 2016

Source: Office for National Statistics (ONS) (2018), Smoking Inequalities in England, 2016

Smoking prevalence and health inequalities

Smoking rates are much higher within deprived communities and certain groups. Smoking is around twice as common amongst people with mental health disorders, and more so in those with more severe diseases. The life expectancy of those diagnosed with a mental health illness is on average 10-20 years less than someone without a mental health diagnosis and the main reason for this difference in life expectancy is due to smoking4. Although smoking is often considered to be stress-relieving, research shows that mental health does not worsen as a result of quitting smoking, and is in fact associated with reduced levels of anxiety and depression5.

Lesbian, gay and transgender communities are also significantly more likely to smoke, as are long-term unemployed, and some minority ethnic groups, which also have gender disparities.

Smoking is the biggest cause of health inequalities in the UK, accounting for half of the difference in life expectancy between the richest and poorest. More people in disadvantaged communities smoke, where smoking is more socially accepted. Poorer smokers are usually more addicted and smoke more each day.

On average, all smokers make similar numbers of quit attempts each year but well-off smokers are much more likely to succeed. To reduce health inequalities it is vital that support to quit is tailored to the needs of poorer and more disadvantaged smokers who find it harder to quit.

Approximately half of all smokers in England work in routine and manual occupations. Workers in manual and routine jobs are twice as likely to smoke as those in managerial and professional roles and unemployed people are twice as likely to smoke as those in employment.

For smoking prevalence amongst the routine and manual workers section of the population, England shows a gradual downward trend up to 2019 and smoking prevalence in this group is currently 23.2%. In Blackpool there was a steeper decline in prevalence amongst this group than seen across the country as a whole, from 44.0% in 2012 to 29.8% in 2018, before increasing again to 36.8% in 2019. In 2020 the estimated prevalence in Blackpool among adults in routine and manual occupations was 26.2% compared to 21.4% nationally, however these figures should not be compared to previous years due to changes in definition and methodology6.

Smoking during pregnancy / smoking status at time of delivery (SATOD)

Smoking during pregnancy can cause serious pregnancy-related health problems and have detrimental effects on the development of the baby and health of the mother. Statistics on smoking during pregnancy and women's smoking status at time of delivery (SATOD) are available on the dedicated Blackpool JSNA Smoking in Pregnancy page.

Health costs of tobacco in Blackpool

Smoking related mortality

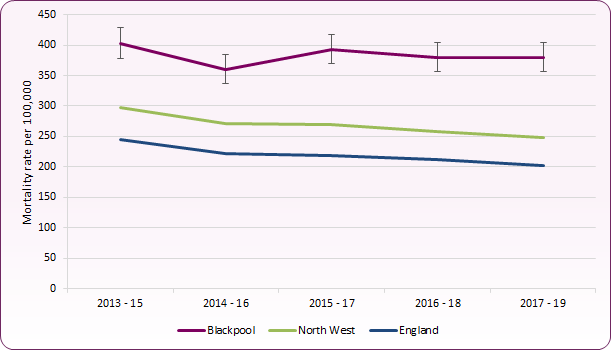

Figure 3 shows the estimated rate of deaths per 100,000 of the population, aged 35+, that are attributable to smoking. In 2017-19 this equated to around 1,000 deaths in Blackpool at a rate of 379.9 per 100,000 population, significantly higher than the national average (202.2 per 100,000) and the third highest rate in the country. Whilst smoking-attributable mortality has been gradually falling in England and the North West, numbers and rates in Blackpool have remained relatively steady.

Figure 3 - Trend in smoking attributable mortality, Blackpool, North West and England

Source: PHE, Local Tobacco Control Profiles for England

Source: PHE, Local Tobacco Control Profiles for England

A breakdown of smoking-attributable deaths and mortality rates for smoking-related disease provides a more detailed understanding of the impact of smoking on mortality (Figure 4). Smoking attributable death rates and mortality rates for smoking related cancers in 2017-19 were significantly higher than the national rate for all causes except oral cancer. Smoking attributable deaths to strokes and heart disease were the second and third highest rates in the country respectively. Blackpool's mortality rate for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) rose steadily from 68.3 per 100,000 in 2007-09 to 103.8 per 100,000 in 2016-18, though fell slightly to 96.5 in 2017-19.

Figure 4: Smoking attributable deaths and mortality rates (per 100,000) from smoking-related disease 2017-19

| Smoking- Attributable Deaths | Blackpool | England |

|---|

| Number | Rate | LA Rank (1=worst) | Rate |

|---|

| Heart disease |

157 |

59.7 |

3rd |

29.3 |

|---|

| Stroke |

42 |

16.2 |

2nd |

9.0 |

|---|

| Cancer |

376 |

142.7 |

7th |

89.6 |

|---|

| |

| Mortality Rate | Number | Rate | LA Rank | Rate |

|---|

| Lung cancer |

336 |

76.5 |

16th |

53.0 |

|---|

| Oral cancer |

27 |

6.3 |

28th |

5.6 |

|---|

| COPD |

423 |

96.5 |

7th |

52.8 |

|---|

Source: PHE Local Tobacco Control Profile for England

Blackpool also has the highest estimated level of Potential Years of Life Lost (PYLL) due to smoking related illness, with a 2016-18 rate of 2,819 per 100,000, compared to the England average of 1,313.

Smoking related ill-health and smoking attributable hospital admissions

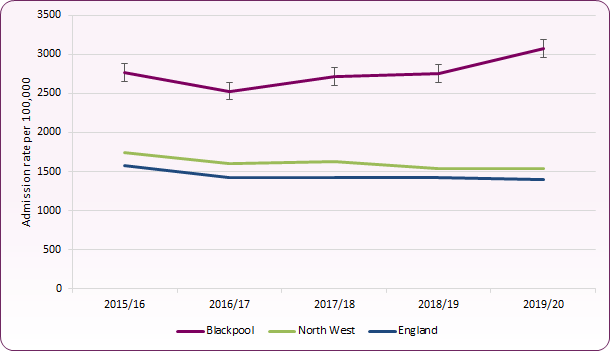

Blackpool has the highest rate of smoking attributable hospital admissions of any local authority in the country. This indicator aims to quantify the scale of preventable hospital admissions due to smoking related conditions. High smoking attributable admission rates are indicative of poor population health and high smoking prevalence. Blackpool has seen a rise in smoking attributable hospital admissions, from 2,528 per 100,000 in 2015/16 to 3,071 per 100,000 in 2019/20 (Figure 5).

Figure 5:Trend in smoking attributable hospital admissions, Blackpool, North West and England

Source: PHE, Local Tobacco Control Profiles for England

Source: PHE, Local Tobacco Control Profiles for England

Smoking related hospital registration and admission rates highlight that rates for lung, oral and oesophageal cancer registrations and COPD admissions are significantly higher than England averages, with oral cancer and oesophageal cancer registration rates the highest in the country (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Smoking related hospital registrations and admissions - numbers and rates (per 100,000 pop.)

| | Blackpool | England |

|---|

| Number | Rate | LA Rank (1=worst) | Rate |

|---|

| Lung cancer registrations (2016-18) |

481 |

112.2 |

17th |

77.9 |

|---|

| Oral cancer registrations (2016-18) |

108 |

25.6 |

1st |

11.3 |

|---|

| Oesophageal cancer registrations (2016-18) |

99 |

23.6 |

1st |

7.5 |

|---|

| COPD emergency admissions (2019-20) |

715 |

820 |

8th |

163 |

|---|

Source: PHE Local Tobacco Control Profile for England

Smoking during pregnancy and exposure to secondhand smoke can lead to premature birth, low birth weight and poor infant health7. For the period 2016-18 period, Blackpool's premature birth (less than 37 weeks gestation) rate of 103.6 per 1,000 births was significantly higher than the national rate of 81.2 per 1,000. In 2019, 3.66% of term babies had a low birth weight (below 2.5kg), slightly higher than the England rate of 2.9%.

Societal costs of smoking in Blackpool

The total burden caused by tobacco products more than outweighs any economic benefit from their manufacture and sale. Action on Smoking and Health (ASH) provide estimates of the cost of smoking to Blackpool. 2022 estimates (based on 2019 prevalence data) suggest the economic cost of smoking in Blackpool is £64.77 Million per year. The estimated costs to Blackpool of smoking to include:

-

- £7.07 Million in healthcare costs (hospital admissions and primary care costs)

- £5.15 Million is social care costs (residential and domiciliary care)

- £1.32 Million in fire costs (deaths, injury, property damage, and fire & rescue cost)

- £51.23 Million productivity costs (lost earnings, unemployment and early death)8

Vaping and electronic cigarettes

Electronic cigarettes ('e-cigarettes'), or vapourisers ('vapes') are electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) that were developed in China more than 15 years ago. They are battery operated devices that do not contain tobacco but operate by heating nicotine and / or other chemicals, including propylene glycol and glycerol, into a vapour that is inhaled.

There are three main types of electronic cigarettes or vapourisers:

-

- Disposable products (non-rechargeable) that can look similar to tobacco cigarettes

- A vape / electronic cigarette kit that is rechargeable with replaceable pre-filled cartridges

- A vape / electronic cigarette that is rechargeable and has a tank or reservoir which has to be filled with liquid, often containing nicotine

There are approximately 3 million vapers in the UK, with 7% of men and 5% of women nationally reporting that they currently use e-cigarettes9. Vaping prevalence is lower than smoking prevalence across all groups of adults10.

In terms of young people, a 2021 survey conducted by Action on Smoking and Health (ASH) found that the majority of 11-17 year olds in the UK have never tried or are unaware of e-cigarettes (88.2%) which has been fairly consistent since 2017. Current use of e-cigarettes among 11-18 year olds is higher among current smokers (41.8%) than former smokers (13.9%) and very low among those who had never smoked, with only one 'never smoker' reporting vaping daily11.

Whilst there is limited up-to-date local data about the prevalence of e-cigarette use in Blackpool, a Blackpool Health and Wellbeing Board survey of health behaviours in 2014 found that 8% of respondents used e-cigarettes: just over 3% daily and around 5% less frequently. A further 8% had used e-cigarettes but didn't any more. People aged 25-44 were significantly more likely to use e-cigarettes than older people, and those aged 16-24 and not in work were most likely to report having used e-cigarettes in the past but having stopped12.

E-cigarettes are increasingly being used by smokers to help quit smoking. A recent Public Health England review found that vaping poses a small fraction of the risk of smoking and that when e-cigarettes are used as part of a quit attempt, success rates are comparable with or higher than licensed medication alone13. The full risks of e-cigarette use have not yet been established and it is not known whether some of the contents of electronic cigarettes (e.g. flavouring products) could be damaging to people’s health. However, if used as a replacement to smoking a reduction in overall risk of adverse health is likely14.

A recent report on vaping in England10, commissioned by Public Health England found that:

- Vaping and smoking prevalence among young people in England both appear to have stayed the same in recent years and should continue to be closely monitored.

- Enforcement of age of sale regulations for vaping (and smoking) needs to be improved.

- Misperceptions of the relative harms of smoking and vaping should be addressed.

- More research is needed on the apparent differences in the prevalence of smoking and vaping in different socioeconomic groups among young people (higher in more advantaged groups) and adults (higher in more disadvantaged groups).

- More research is needed on the addictiveness of different types and strengths of nicotine vaping products among young people and the extent to which they are using illegal products.

2021 guidance by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) also highlighted that whilst e-cigarette use is likely to be "substantially less harmful than smoking" there is currently insufficient evidence about long-term harms. The guidance recommends that clear, consistent and up-to-date information is important for adults interested in using e-cigarettes to stop smoking, and people should only use e-cigarettes for as long as they help prevent them from going back to smoking. The guidance also recommends that young people are discouraged from using e-cigarettes due to the potential higher chance of smoking in the future, and the recommended approach to treating tobacco dependence for those aged 12 to 17 is to consider Nicotine Replacement Therapy (NRT) together with behavioural support15 (see also JSNA Tobacco Use in Children and Young People page).

National and local policies

Local strategies

Tobacco FREE Lancashire: Towards a Smokefree Generation 2023-2028  (1887Kb)

(1887Kb)

The Tobacco Free Lancashire strategy has the overarching framework of Smokefree – to reduce the damaging impact of tobacco by helping people to quit smoking, reducing the availability of illicit tobacco and challenging the social norm of smoking. It is seeking to create more smokefree environments and spaces across communities and challenge the norm of smoking.

The Tobacco Free Lancashire strategy has been developed in line with the Tobacco Control Plan for England, which sets out the ambition to achieve the smokefree ambition of lowering smoking prevalence to less than 5% in every neighbourhood by 2030 through:

-

- preventing children from taking up smoking in the first place

- stamping out inequality for example smoking in pregnancy

- supporting smokers to quit

The strategy has prioritised the following areas based on detailed local intelligence in order to reduce health inequalities and improve quality of life by reducing smoking prevalence in the following groups:

-

- pregnancy

- people with mental health conditions

- people with long-term conditions

Directors of Public Health position statement on nicotine vaping September 2023  (1550Kb)

(1550Kb)

Produced collaboratively by the public health directors across Lancashire and South Cumbria, it represents the agreed position of public health with regard to nicotine vaping.

The position statement accepts the priority should be on tobacco control, but acknowledges the significant concerns around vaping including the use by children and the health risks; easy access to vapes as well as the direct and indirect advertising/marketing of the products; the rise in availability of illicit products; the environmental impacts of single-use vapes; the role of vapes in helping adults to quit smoking; and the urgent need to provide clarity to NHS provider services and settings on the status of vapes in NHS Smokefree Policies.

National strategies

The World Health Organisation Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, the NHS Long Term Plan and the Department of Health’s 'Towards a Smokefree Generation: A Tobacco Control Plan for England' are some of the key strategic documents which inform service design and delivery.

NICE guidance NG209 'Tobacco: preventing uptake, promoting quitting and treating dependence' provides advice, quality standards and information services for health, public health and social care. It also contains resources to help maximise use of evidence and guidance.

Services

Blackpool's NHS Tobacco Addiction Service

We believe that it is never too late to help our residents to stop smoking and we know that no matter what a person’s health status is, stopping smoking is always beneficial.

In November 2019 it was agreed by the Fylde Coast CCG and Blackpool Public Health that:

- The CCG will take responsibility for funding healthcare based stop smoking services (inpatient and maternity) as recommended by the NHS Long Term Plan

- Blackpool Council will re-invest funding to re-establish an effective community stop smoking model

- The CCG will include Nicotine Replacement Therapy on the formulary

- The NHS and local authority will work in partnership to design and manage stop smoking services.

A Fylde Coast Stop Smoking Delivery Group was established to progress these recommendations. The overall aim is to provide equitable access to tobacco addiction treatment across the Fylde Coast and to facilitate a smooth transition for individuals between inpatient services, maternity services and community services.

Blackpool's NHS Stop Smoking Services began in January 2021, providing support to Blackpool residents as part of the wider Fylde Coast pathway. The service treats smoking as an addiction first and foremost, helping smokers to understand that the highly addictive nature of nicotine (contained within tobacco) is one of the main reasons why it is so hard to stop smoking.

The service is open to anyone aged 12 and over who lives or works in Blackpool and wants to give up smoking, but the focus of this service is to reduce smoking-related health inequalities and so there will need to be an emphasis on community engagement and working with key target groups - those most vulnerable to tobacco addiction. Smokers are offered a combination of pharmacotherapy and psychological support to help them to ‘quit’ and to remain tobacco free long term.

Our recommended approach regarding the delivery of pharmacotherapy is based upon our local understanding that for a variety of reasons, it is very hard for some people who live in Blackpool to stop smoking (reflected in historic and current high rates of smoking). Therefore, we want to make quitting smoking as easy as possible and to minimise barriers. For this reason we recommend a model of ‘direct supply’, which means that the service will offer pharmacotherapy direct to the client at the time of their appointment and ongoing psychological support and pharmacotherapy for up to twelve weeks. We want there to be as few steps as possible for the clients in their smokefree journey.

Alongside these services, Blackpool residents can access ‘My Quit Route’ which is the free Smokefree Blackpool app, and can access free Nicotine Replacement Therapy (NRT) including patches, gum and lozenges, when they register for Stop Smoking Support through participating GP's, Pharmacies or the Smokefree Blackpool Helpline.

Recommendations

Key recommendations to address smoking in Blackpool include:

- Implement integrated stop smoking support between Acute and Community Services and in particular the development of new services for inpatients and pregnant women, in line with the NHS Long Term Plan

- Ensure that services reflect Blackpool’s ambition to reduce health inequalities by focusing on deprived communities and priority groups

- Continue to adhere to the Local Government Declaration on Tobacco Control and ensure tobacco control is part of mainstream public health work

- Make tobacco less accessible by considering licensing sales/local initiatives and reducing the flow of illicit and illegal tobacco products into Blackpool

- Reduce exposure to Second Hand Smoke by working towards a Smokefree Blackpool

- Ensure that tobacco control is prioritised in cross-cutting policies, education, guidance and funding

- Work with workforce and communities to change the cultural norms around smoking.

[] Office for National Statistics, 2020. Adult smoking habits in the UK: 2019. Accessed 6 May 2021.

[] Office for National Statistics, 2020. Smoking prevalence in the UK and the impact of data collection changes: 2020. Accessed 25th December 2022.

[] Office for National Statistics, 2018. Likelihood of smoking four times higher in England’s most deprived areas than least deprived. Accessed 6 May 2021.

[] ASH, 2019. Factsheet No.12: Smoking and Mental Health [pdf] Available from https://ash.org.uk/information-and-resources/fact-sheets/health/smoking-and-mental-health/

[] Taylor G.M.J., Lindson N., Farley A., Leinberger-Jabari A., Sawyer K., te Water Naudé R., Theodoulou A., King N., Burke C., Aveyard P. Smoking cessation for improving mental health. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2021, Issue 3.

[] Public Health England, Local Tobacco Control Profiles.

[] Department of Health. Towards a Smokefree Generation: A Tobacco Control Plan for England, 2017.

[] ASH, 2020. ‘Ready Reckoner’ v7.0, October 2019. Available from ASH Ready Reckoner - Action on Smoking and Health (Accessed 4 May 2021).

[] NHS Digital, 2020. Health Survey for England 2019 (Accessed 6 May 2021).

[] McNeill, A., Brose, L.S., Calder, R., Simonavicius, E. and Robson, D. (2021). Vaping in England: An evidence update including vaping for smoking cessation, February 2021: a report commissioned by Public Health England. London: Public Health England.

[] ASH, 2021. Use of e-cigarettes among young people in Great Britain, June 2021 (ash.org.uk).

[] Blackpool Health and Wellbeing Board, 2015. Health Behaviours in Blackpool: A summary of the Blackpool Lifestyle survey 2015.

[] Public Health England, 2020. Vaping in England: 2020 evidence update summary (www.gov.uk) (Accessed 10 May 2021)

[] Committee of Toxicity of Chemicals in Food, Consumer Products and The Environment (COT). Statement on the potential toxicological risks from electronic nicotine (and non-nicotine) delivery systems (E(N)NDS - e-cigarettes). July 2020.

[] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Tobacco: preventing uptake, promoting quitting and treating dependence. NICE Guidance [NG209], November 2021.