Child Sexual Exploitation

Last Modified 31/03/2022 15:16:26

Share this page

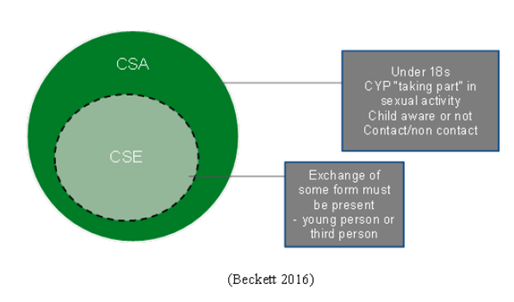

Child sexual exploitation (CSE) is not synonymous with sexual abuse. Recent Public Health England (PHE) guidance emphasises that CSE and sexual abuse are not interchangeable, but that “CSE is a form of child sexual abuse.” Unlike more general sexual abuse, CSE infers that there has been “some form of exchange” and “the child receives ‘something’ in return for the sexual activity.” The PHE guidance illustrates this relationship with a diagram representing that CSE falls within, but must be distinguished from, the wider definition of child sexual abuse1:

Figure 1: The relationship between child sexual exploitation and other forms of sexual abuse

Source: PHE, Child sexual exploitation: How public health can support prevention and intervention, July 2017

The full definition of CSE proposed by the Department of Education is used by PHE:

“Child sexual exploitation is a form of child sexual abuse. It occurs where an individual or group takes advantage of an imbalance of power to coerce, manipulate or deceive a child or young person under the age of 18 into sexual activity (a) in exchange for something the victim needs or wants, and/or (b) for the financial advantage or increased status of the perpetrator or facilitator. The victim may have been sexually exploited even if the sexual activity appears consensual. Child sexual exploitation does not always involve physical contact; it can also occur through the use of technology.” (Department for Education 2017:5)

The form of ‘exchange’ inherent to CSE can take many forms, including: online sexual abuse; peer on peer abuse; CSE within gangs; and international child trafficking.

The NSPCC defines Online Child Sexual Exploitation as a means of “persuading” or “forcing” young people to engage in sexual activity online.This exploitation can take different forms, including:

-

-

Online grooming2

-

Being encouraged to take part in sexual conversations and activities streamed via webcam2

-

The exchange of pornographic images of children, often across trans-national networks3

-

Cyber-bullying, including sexting2,4

The internet provides many opportunities for young people. More than 90% of teenagers now have access to the internet at home. With the widespread use of mobile phones and tablet devices, it is increasingly difficult for parents to monitor their child’s online activities. The Child Exploitation and Online Protection Centre (CEOP) estimates that, in 2012, 24% of 8-11 year olds and 55% of 12-15 year olds used the internet unsupervised. When used appropriately, computers and mobile devices can be a vital resource for learning, and a way to maintain and expand social networks. However, there are also significant dangers associated with internet use. Interacting with online communities can leave children and young people vulnerable to exploitation.3

The CEOP defines online grooming as “developing the trust of a young person or his or her family in order to engage in illegal sexual conduct.” The CEOP includes in this definition:3

-

-

Causing a child to watch a sexual act, eg sending sexually themed adult content or images and videos featuring child sexual abuse to a young person,

-

Inciting a child to perform a sexual act, eg by threatening to show sexual images of a child to their peers and parents (eg self-produced material or even a pseudo-image of the child,

-

Suspicious online contact with a child, e.g asking a young user sexual questions,

-

Asking a child to meet in person; befriending a child and gaining their trust etc,

-

Other grooming…e.g using schools or hobby sites such as the Scouts or Girl Guides to gather information about their particular children, their location and future events where the child may be present; presenting as a minor to deceive a child online etc.

The CEOP notes that it is difficult to accurately report data related to child abuse; any estimates reflect national and international trends.3 This is partly due to difficulties in accurately monitoring regional data, and a reflection of the fact that the majority of activities falling under the definition of Online CSE are likely to be unreported. However, even conservative estimates suggest a widespread problem:

-

-

Barnado’s found that 60% of young people aged 13-18 have been asked to create and share a sexually explicit image of themselves, and that as much as 88% of that self-created content is shared elsewhere on the internet after being uploaded4

-

The CEOP estimates that 20% of child abuse images online were self-generated3

-

Whilst any child can be groomed online, the most vulnerable group is Caucasian girls aged 11-14. Children depicted in online pornography are commonly even younger, with 80% of the children in online pornographic images less than 10 years old.5

Signs of online grooming

Childline emphasises that online grooming can happen in any online community, including: online gaming groups; social networking sites; instant messaging and photo exchange apps; and online forums. Signs of online grooming young people can be warned about include:6

-

-

Encouraging the young person to keep the relationship a secret,

-

Sending multiple messages to the young person, often through multiple forums simultaneously,

-

Gathering information about the young person’s family and level of internet supervision to evade detection,

-

Giving inappropriate comments about the young person’s appearance, which may progress to more overt sexual references,

-

Blackmailing a young person – for example, asking them to send a naked or inappropriate image, and then threatening to share this with others unless they produce more images or videos.

International Child Abuse

The CEOP identified “the proliferation of indecent images” as one of the most important threats related to Online CSE.3

The majority of images of child abuse are not shared for financial gain.3,5 The European Cyber Crime Centre notes that abusers are making increasingly sophisticated efforts to communicate with each other and evade detection. Online communities of paedophiles co-operate with each other to share images of abuse, and often form hierarchies in which abusers with advanced technological knowledge share information and methods of evasion with those less technically experienced. Methods of evasion can include creation of Virtual Private Networks, use of encryption software and password protection and secure clouds. Abusers may informally share knowledge of how to abuse children whilst escaping detection by the authorities; often this is confined to an exchange of information between similarly motivated individuals, and there is no commercial profit.5

Exchange of child abuse images for financial gain has been decreasing in recent years. However, the European Cyber Crime Centre estimates that approximately 8.5% of child abuse material is the result of organised efforts to profit from child abuse across international borders. This usually focuses on exploitation of children in developing countries ‘on demand’ for abusers in more developed countries to view via webcam, for a fee. Often these fees are paid securely and via online currencies to avoid detection.5

The CEOP notes that locations of transnational child abuse involving UK abusers tend to follow general travel trends. Whilst locations previously associated with prolific child sexual exploitation, including Thailand, the Phillipines and Cambodia have recently committed considerable resources to reducing Online CSE, it is expected that this will result in displacement of abuse to other countries, including South American nations.3

Cyber Bullying and Texting

It is important to remember that adults are not the only perpetrators of Online CSE.2,4,6 A lot of exploitation occurs between children and young people themselves. This is frequently in the form of peer pressure to exchange self-generated sexually explicit images. This includes ‘sexting’ which the NSPCC defines as sharing “sexual, naked or semi-naked images of themselves or others, or sends sexually explicit messages.” This is often referred to as “trading nudes”, “dirties” or “pic for pic.” It is illegal to possess an explicit image of a child or young person under the age of 18, and this applies even if the image was taken and shared by the young person in the image.7

Cyber-bullying does not have to be confined to sexting. Any inappropriate involvement of a child or young person which incites them towards sexual conduct or conversations they do not yet have the maturity to process could be termed Online CSE.

The NSPCC emphasises the importance of giving children “age appropriate” education about how to protect themselves from inappropriate peer pressure and Online CSE.2,7 The NSPCC and other organisations including Barnado’s and Childline have educational tools for young people, parents and teachers about how to remain safe online. Barnado’s notes this education should emphasise the important message that children should remain aware that people are not necessarily whom they claim to be online, and that they should not share images or information they would not want to become publicly available.4 It is important for young people to realise that any sharing of images or messages on the internet is no longer under their control once they have sent it, and that this applies equally to a forum where they may see information as temporary, such as Snapchat; it is still possible for screenshots to be shared by others.

Child sexual exploitation is not always committed by adults.8 There is a growing awareness that children and young people may also be vulnerable to exploitation by peers,8-10 Barnado’s and the NSPCC refer to this as “peer on peer child sexual exploitation.” 65.9% of those under 18 who report “contact abuse” attribute this to a person also under the age of 18.9, 11 The perpetrators of this abuse are also often referred to as children or young people with “harmful sexual behaviours” (HSB).10, 12

Definition

Hackett et al define Harmful Sexual Behaviour (HSB) as: “sexual behaviours expressed by children and young people under the age of 18 years old that are developmentally inappropriate, may be harmful towards self or others, or be abusive towards another child, young person or adult.”10

What behaviours constitute Peer on Peer CSE/Harmful Sexual Behaviour?

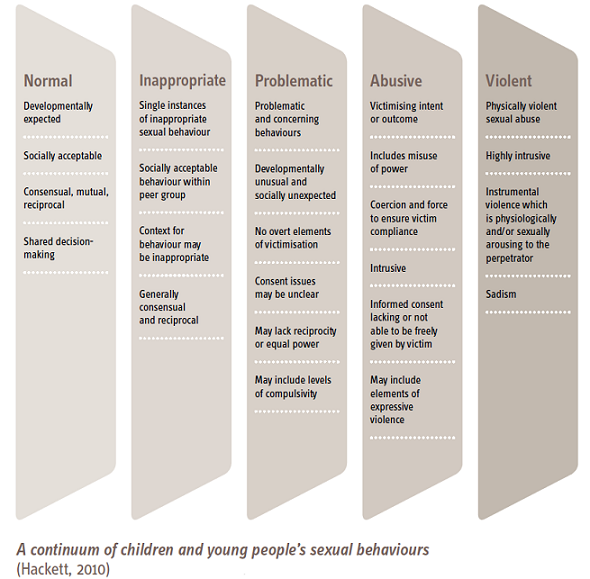

Hackett et al emphasise that “developmentally inappropriate” sexual behaviours in young people are complex, and can encompass a range of behaviours. Hackett devised a spectrum of behaviour which may be observed in those under 18, ranging from “normal” reciprocal experimentation with peers to the most extreme form of “violent” harmful sexual behaviour.

Figure 2: A continuum of children and young people’s sexual behaviours

Source: NSPCC, Responding to harmful sexual behaviour including peer to peer abuse – an evidence informed framework

Hackett’s work emphasises that the sexual behaviour of young people must never be considered out of context, or as isolated incidents. Instead, it is important to consider the overall development and circumstances of the young person, and to consider that the perpetrator may also have been a victim of CSE, or have other complex needs.10 The continuum emphasises that “abusive” and “violent” behaviour is distinguished from less severe evidence of HSB by the absence of informed consent, and “victimisation” which implies a “misuse of power.”9, 11

Barnado’s and the NSPCC emphasise that peer on peer CSE can occur in a variety of environments, including: in school or college; online; and in communities including youth groups and informal gatherings of young people.8, 9 Both highlight the subversive nature of peer on peer abuse, and that it is perhaps the most under-reported form of CSE.8-10 This type of abuse can take many forms, including any form of coercion to participate in sexual activity.10 There have been many instances of young people being blackmailed by peers who possess sexually explicit images of them. These can be used to exert control over victims, either for psychological intimidation or to coerce the young person into further sexual activity under threat of revealing the images to family and friends, or posting them on social media. Any attempt to coerce or manipulate a young person into sexual activity by another person under the age of 18 constitutes peer on peer abuse.8

Barnado’s summarises potential signs that a young person is the victim of peer on peer CSE:8

Who is at risk of Peer on Peer CSE/Harmful Sexual Behaviour?

All young people are at risk of peer on peer CSE, and all adults who have contact with young people should be alert to its signs.8,10 However, certain groups may be at higher risk of becoming the victim of this type of CSE, or of engaging in HSB themselves. The majority of victims of CSE are girls. Barnado’s emphasise it is likely that this type of abuse in boys is even more under-reported than in girls, as a result of increased stigma. However, Hackett et al note that even taking account of this, the vast majority of victims are young women.10 Barnado’s have also expressed concern that young people in BME communities may also feel an increased sense of stigma related to CSE which may discourage them from voicing concerns.8

Young people who come from complex family circumstances, particularly homes where domestic abuse has occurred, may be more likely to consider coercive behaviour to be “normative” and may be less likely to recognise it as abuse. Young people who have been the victim of CSE committed by an adult may also be vulnerable to HSB from peers.8,10 Hackett et al also note that young people with learning difficulties, or mental health problems may also be especially vulnerable.

The perpetrators of Peer on Peer CSE/Harmful Sexual Behaviour

The complexity of peer on peer CSE is increased by the fact the perpetrator may also be a victim of CSE, or be in need of support. Almond et al found that approximately 70% of young people engaging in HSB towards others under the age of 18 could be classified into one of three groups:10,13

-

-

“Abused” young people who may have been the victim of CSE themselves, and are likely to have very complex needs. These young people should be recognised as being “in need.”

-

“Delinquent” young people whose behaviour is part of wider concerns about behaviour, which may include other antisocial or criminal behaviour

-

“Impaired” young people who may have a learning disability or mental or physical health problems which substantially effect their development

Hackett et al and organising including Barnado’s, recognise that the needs of the perpetrators of abuse in these circumstances may be equally, or more, complex than those of victims.8,10,13

Responding to peer on peer sexual abuse/Harmful Sexual Behaviour

All adults who work with young people should be alert to the existence of peer on peer abuse and recognise its signs. Evidence of peer on peer abuse can be subtle. Tackling this form of abuse is made more difficult by its under-reporting, and by the fact that the perpetrator may also have complex needs. There is a consensus that early intervention and inter-agency collaboration is particularly important in tackling peer on peer CSE.8,10

Barnado’s argues that young people can be supported in building resilience to peer on peer CSE through self-esteem building, and education regarding online safety.8 Building awareness in young people that images can often be stored in covert ways (for example, screenshots taken from snapchat) they may not be aware of, and that images take of them may leave them more vulnerable to manipulation and sexual exploitation.4

It is well recognised that young people who belong to gangs are at higher risk of CSE.14-16 The Office of the Children’s Commissioner’s Inquiry Into Child Sexual Exploitation in Gangs and Groups define gangs as: “relatively durable, predominantly street-based, social groups of children, young people and, not infrequently, young adults who see themselves, and are seen by others, as affiliates of a discrete, named group who:

-

engage in a range of criminal activity and violence;

-

identify or lay claim to territory;

-

have some form of identifying structural feature;

-

are in conflict with similar groups.”

Problems associated with local data collection

The publication of two reports by the Office of the Children’s Commissioner’s Inquiry Into Child Sexual Exploitation in Gangs and Groups is the most comprehensive work to date on the issue of CSE within gangs. The authors note familiar trends of poor inter-agency collaboration; insufficient attention to the subjective experience of the young people involved; and deficiencies in local data collection and co-ordination of response.15,16

Difficulties in local data collection are particularly salient regarding CSE within gangs15 and they argue that CSE is persistently underestimated. There are significant inconsistencies in robustness of local data collection, with some local authorities committing more resources to identification of CSE than others. There are also inconsistencies in definitions of CSE and gang-related incidents. Inefficient inter-agency collaboration contributes to deficiencies in data collection. The result is that national estimates regarding the incidence and prevalence of CSE are likely to be significantly lower than the true picture, and multiple artefacts are present within the data. The report emphasises the need for local authorities to recommit to data collection and inter-agency collaboration, although the covert nature of CSE, particularly within gangs, poses significant challenges to this goal.16

Behaviour associated with Gang-related CSE

The Inquiry reveals shocking trends about the nature of gang related CSE15,16 and Barnados identifies gang related CSE as occurring both within and between gangs.14 Within a gang, members may be coerced into performing sexual acts as part of initiation rites, or in order to obtain “protection” from senior members of the gang. Young women related to gang members, including girlfriends and sisters, or other female relatives, may also be targeted by rival gangs as an act of aggression or retaliation. Young women subjected to these forms of abuse are often referred to as “wifeys” or “links.”14

The Inquiry highlights that this form of sexual abuse often attempts to maximise humiliation and suffering for victims. It reveals that repeated sexual abuse, often by groups of men who assault young women in quick succession, is commonplace. This is much more likely to include anal rape or oral abuse than vaginal intercourse without consent. The authors heard evidence from experts in CSE, who argued this was likely a consequence of trends in pornography, and a desire to maximise domination and humiliation of the victim. These extreme forms of abuse may also be linked to physical violence, including threating victims with weapons to ensure submission to sexual assault. Widespread emotional abuse also occurs, with gang members using threat of sexual or physical violence to control victims.16

Who is at risk of Gang-Related CSE?

The Inquiry documents 2,409 cases of CSE in a gang context between April 2010 and March 2011, with a further 16,500 young people estimated to be at risk. According to government data, more than 1.1 million children currently live in a postcode known to contain local gangs.16 The victims of gang related CSE are overwhelmingly young women, although young men are also at risk of sexual violence in this context. The vast majority of gang members are aged between 13 and 25. Female gang members, and female relatives of male gang members, are at particular risk.14

Signs that a young person may have been the victim of Gang-related CSE

Young people who are the victims of gang related CSE may demonstrate similar signs to young people who are the victims of other forms of CSE. In particular, possible signs include:14

-

-

Unexplained expensive accessories or gifts

-

Engagement with criminal activity

-

Evidence of drug or alcohol abuse

-

Recent change in behaviour/personality

Policy regarding Gang-Related CSE

The Inquiry outlines the See Me, Hear Me national framework15 to address some of the problems and inconsistencies they found in local responses to CSE. It emphasises the need for inter-agency collaboration; the need for a young-person centred approach prioritising the experience of victims; and the need to focus on local data collection which gives a truer picture of the extent of the problem. This will be particularly important within local authorities which have known problems related to gangs.

Academic and grey literature acknowledges that child trafficking is a significant problem in the UK.1,17 Children and young people who are trafficked may be subject to a range of abuse and exploitation including: financial exploitation and forced labour; forced marriage; and sexual abuse.18 Due to the covert nature of child trafficking networks, this problem is under-reported and the evidence base regarding its extent and effects is comparatively small.18,19 The limited literature available has emphasised the importance of training healthcare professionals to recognise signs that young people have been trafficked.19-22 The literature also acknowledges this problem to be an international public health crisis.23

UNICEF defines a child as being trafficked if “he or she has been moved within a country, or across borders, whether by force or not, with the purpose of exploiting the child.”24

Risk factors for trafficking

-

Being female1,24,25

-

Frequently missing from home or local authority care26

-

Being from a non-White background27

-

Being a victim of other forms of sexual abuse and exploitation28

-

Being homeless28

-

Having a learning disability28

Signs that a child or young person may have been a victim of trafficking

Literature reviews have focused on the importance of educating healthcare workers to recognise the signs of child trafficking.17,19-23 Barnardo's has also drawn attention to the distinction between warning signs of trafficking upon entry to the UK and once in the UK. These risk factors are summarised in the table below:

Figure 3: Warning signs of trafficking

| Signs of trafficking upon entry to the UK | Signs of trafficking once within the UK |

|---|

|

Illegal entry

|

Unexplained/unidentified phone call when in care

|

|

No passport or identification, or false documents

|

Evidence of physical or sexual abuse, or pregnancy

|

|

Accompanied by an adult who will not leave the child under any circumstances

|

Frequently missing from care or home

|

|

A 'prepared' story

|

Cared for by adults who are not the child's parents

|

|

A journey arranged by someone other than the travellers

|

Other unrelated children living at same address

|

|

Child or young person is withdrawn or appears afraid

|

Not registered in school or with a GP

|

|

Unable to give personal details such as address

|

Expresses excessive fear of deportation

|

|

No cash but may have a mobile phone

|

Evidence of financial exploitation including begging for money; being required to earn a minimum sum each day; or rarely leaving a place of residence

|

|

Source: Barnardo's, Child Trafficking Advocacy - Trafficking Risk Factors, 2017

|

Sexual exploitation networks have received considerable recent media attention. Independent inquiries into networks of CSE in Rotherham and Rochdale have revealed that CSE is often systematic and extensive.29,30 The Jay Report into CSE in Rotherham makes the “conservative estimate” that approximately 1,400 children were sexually exploited in Rotherham between 1997 and 2013. Evidence of abuse was revealed in numerous contexts including: fast food outlets; taxis; and hotels.

In many cases, young people were systematically groomed and subjected to prolonged abuse. In some cases this involved inducing young people to recruit peers, and targeted grooming of vulnerable young people through social media. There was evidence of trafficking within the UK, particularly in the North of England.29,30

Risk factors for victimisation by CSE networks in the UK

The Jay Report identifies some important risk factors for CSE:29

-

Substance abuse and alcohol dependence

-

Parental alcohol and substance abuse

-

Mental health problems

-

Domestic violence

-

Truancy and school refusal

-

Repeatedly missing from home

-

History of neglect/other child abuse

Lessons learned from Rotherham and Rochdale

The reports of public inquiries into CSE networks in Rotherham and Rochdale reveal important lessons for other local authorities including:

Figure 4: Key reccommendations of independent public inquiries into Child Sexual Exploitation networks within Rotherham29 and Rochdale30

| Recommendations of Rotherham Inquiry | Recommendations of Rochdale Inquiry |

|---|

|

Thorough, up-to-date risk assessments of children known to have been affected by CSE.

|

A need for leadership within the CSE team to secure short, medium and long term goals.

|

|

A "more strategic approach" to protecting looked after children, who are often more vulnerable to CSE.

|

Ensure resources allocated to tackling CSE reflect current best evidence, and are targeted towards the prevention and detection of CSE, in addition to prosecution of its perpetrators.

|

|

There is a need to "reach out" to potential victims of CSE not known to services.

|

There is a need to increase awareness about CSE. This should include engagement with the community, those who work with under 18s, and young people themselves.

|

|

A "joint CSE team" with a defined remit and responsibilities should be formed.

|

Use real cases, appropriately anonymised, to facilitate learning.

|

|

A single manager should be responsible for the Joint CSE team.

|

There is a need for an inter-agency approach which makes roles and responsibilities regarding CSE clear.

|

|

In consultation with the LA and police, resources available to the CSE teams should be reviewed, to ensure they are adequate and appropriate.

|

A need to encourage a culture which encourages challenging inappropriate responses to potential CSE, and ensures prompt escalation to managers.

|

|

There should be an inter-agency effort to support children and young people affected by CSE and offer preventative resources.

|

There is a need for national policy to clarify local authority powers regarding licensing and intelligence gathering regarding potential perpetrators.

|

|

Identified victims are likely to require long-term support. Local services should accommodate this and not restrict young people to only short-term support.

|

There is a need to engage with services with experience of CSE to maximise learning opportunities.

|

|

The Safeguarding Board and CSE sub-group should ensure an inter-agency approach to support services for CSE victims.

|

|

|

There is a need for more open engagement with ethnic minority groups regarding CSE. This should include tackling under-reporting of abuse within these groups.

|

|

|

"The issue of race should be tackled as an absolute priority" if this is a factor in local patterns of CSE and child abuse.

|

|

|

All serious case reviews must make the welfare of the child the first priority.

|

|

|

Sources: Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Exploitation in Rotherham 1997-2013, August 2014 and A Reort of the Independent Reviewing Officer in Relation to Child Sexual Exploitation Issues in Rochdale Metropolitan Borough Council During the Period 2006 to 2013, May 2013

|

Although it is currently impossible to accurately estimate the prevalence of CSE at a national or local level, CSE remains an issue in Blackpool and across the county. Research shows that CSE referrals are highly likely to have appeared within social care at some point; two thirds having been registered as a child in need. Exclusions and unauthorised absence from education feature highly in cases, along with missing from home episodes and poor family structures31.

Blackpool experiences considerable levels of disadvantage with many families who are from socially and economically deprived backgrounds and who often have an array of complex needs that require additional support from a range of service providers. Abuse and neglect represent the biggest need areas for safeguarding children in Blackpool and proportions of children in need under these categories are higher than seen elsewhere. The proportion of 'looked after children' is also higher compared to other authorities in England. Information from the Department for Education32 shows:

-

There were 4,202 (14 out of every 100) children in need in Blackpool throughout 2015/16.

-

The Blackpool rate of 1464.9 per 10,000 children is more than twice the national average (667.1 per 10,000).

-

There were 2,521 referrals to Children's Social Care in 2015/16, 20.7% were repeat referrals.

-

364 children were the subject of a child protection plan at March 2016 with 7% recording sexual abuse as one of the reasons for the plan.

-

Half of the Blackpool children on a child protection plan have more than one category of abuse recorded.

-

The rate of children at each stage of the safeguarding process in Blackpool remains well in excess of national and statistical neighbour averages.

Local data does establish that Blackpool is disproportionately affected by many of the risk factors for CSE and there is a significant night-time economy which may make local young people more vulnerable to CSE networks. While the town also has many fast food outlets, taxis and hotels associated with it’s vibrant night-time economy; settings identified as potential risk areas for abuse,29 it has been found that in Blackpool the predominant model is of a white male offending alone, grooming a single victim who is also most likely to be white. There remains no evidence of gang or taxi related offending.33

Findings related to CSE highlighted in the Blackpool Safeguarding Children Board Annual Report 2016-2017 show:

-

-

CSE in Blackpool does not conform to some media stereotypes.

-

Offenders are typically white males operating alone and offending after a process of building a relationship.

-

The most likely offence location is the offenders place of residence.

-

The majority of victims are girls though Blackpool has a significantly higher number of boys recorded as victims than is the case nationally or regionally.

-

The predominant age of victims is between 13 and 15, although there is a trend for increasingly younger children being identified as at risk of CSE.

-

Perpetrators tend to be less than 5 years older than their victim, although some are much older.

-

Social media is likely to have featured as both an initial and ongoing means of contact.

-

There is a strong correlation between being a victim and episodes of missing from home, disrupted education and self-harm.

-

Children in the care of the local authority are considered as being at a higher risk of CSE, which fits with the national picture.

-

During 2016/17, 431 Protecting Vulnerable People (PVP) referrals with a CSE element were made to the Multi-Agency Safeguarding Hub (MASH), an increase from 290 the previous year.

-

The increase is possibly due to reporting of historical abuse or better early identification of CSE in recent practice.

The BSCB Report also details what has been done about CSE in Blackpool and what will be done next.

Key findings relating to CSE from the Safer Lancashire Strategic Assessment 2015: Blackpool District Profile were:

-

-

An increasing number of victims were initially contacted via social media

-

There was an increase in boys/young males being referred

-

The offender profile was 90% male, 93% white

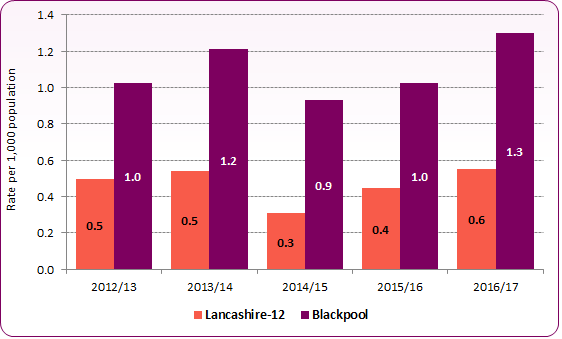

Figures reported by Lancashire Constabulary show that there were 183 reports of crimes with a CSE element in Blackpool in 2016/17, a rate of 1.3 per 1,000 population (Figure 5). This is an increase from 44 in 2015/16 and is significantly higher than the Lancashire average of 0.6 per 1,000. There is considerable variation within Blackpool with rates ranging from 0.1 to 4.3 per 1,000 population at ward level.

Figure 5: Recorded Crime with Child Sexual Exploitation qualifier: Blackpool and Lancashire, rate per 1,000 population

Source: Safer Lancashire, MADE database, District Profile v16.1

Risk factors affecting CSE in Blackpool are:

The Office of the Children's Commissioner's Inquiry into Child Sexual Exploitation in Gangs and Groups (CSEGG)15 also identified 11 indicators of CSE risk in children aged 10+ that can be measured using education, police or other public service datasets, to identify children at risk locally:

-

Child in Need or Children Looked After

-

Children persistently absent from education

-

Children permanently excluded from school

-

Children misusing drugs and/or alcohol

-

Children engaged in offending

-

Children reported missing, or Children reported to be 'absconding' or 'breaching'

-

Children reported as victims of rape

-

Children lacking friends of similar age

-

Children putting their health at risk

-

Children displaying sexually inappropriate behaviour

-

Children who are self-harming or showing suicidal intent.

Evidence shows that any child displaying several vulnerabilities should be considered to be at high risk of sexual exploitation. However, it is important to remember that children without pre-existing vulnerabilities can still be sexually exploited.

Coventry University's rapid evidence assessment of the best evidence34 for identifying and appraising risk indicators for CSE found two significant indicators of increased risk of becoming a victim of CSE; being disabled and being in residential care. A number of potential indicators were also identified including: identity/demographic factors; alcohol and drug misuse; going missing, running away, escaping from abuse, family difficulties; association with gangs/groups; first sexual contact at a young age; frequent and particular types of use of social media; and fewer friends than peers, a poor relationship with parents and an isolated position' combined with a setting in which a trusted relationship is formed. However, the research evidence for these is currently weak.

Section 13 of the Children Act 2004 requires local authorities and other named statutory partners to make arrangements to ensure that their functions are discharged with a view to safeguarding and promoting the welfare of children. This includes planning to prevent children from going missing and to protect them when they do. In fulfilling their statutory roles, the Local Safeguarding Children Board (LSCB) should give due consideration to the safeguarding risks and issues associated with children missing from home or care35.

The National Crime Agency Missing Persons Bureau shows that across England and Wales there were over 127,000 children aged 0-17 years reported missing in 2014/15. The incidents reported related to 60,600 individuals who on average, went missing twice.

-

-

60% of all missing person incidents are related to children

-

54% of child missing incidents were female

-

93% were between the ages of 12-17 years.

-

There are a disproportionately higher number of 12-17 year olds reported as going missing.

-

Approximately half of the missing child incidents are attributable to repeat missing episodes36.

A report by the Children's Society, 'Still Running 3'37 looks into the causes of running away and indicates that family change and conflict play a significant part in children's decisions to run. In addition, there are particularly vulnerable groups of children who are more likely to run away such as disabled children, children with learning difficulties and children in care. It found:

-

-

Family factors are by far the most important determinant of running away.

-

Young people who are not living with family (i.e. in residential care, foster care and other non-family settings) are a particularly high risk group for running away and for running away repeatedly.

-

There are higher than average running away rates amongst young people who defined themselves as disabled and/or as having learning difficulties.

-

There is now substantial evidence of the risks which young people face while away from home. Around 1 in 9 young people who had run away said that they had been hurt or harmed while away from home.

-

Very few young people who run away approach agencies for help while away from home. Additionally, only a minority are reported missing to the police by their parents.

-

A large proportion of young people are visible to informal sources of support (including relatives, parents of friends and neighbours) while away from home and a large proportion are known to friends who appear to be the most common source of support.

-

There is a strong association between recent missing from home and low levels of subjective well-being.

In summary, young people who run away are more likely to have experienced recent family change, are likely to be experiencing poor quality family relationships or to be living away from their family, and are likely to have relatively weak connections with friends and school.

Young people who runaway are at risk of:

-

-

Becoming involved in crime to survive, from stealing to criminal gang involvement

-

Sexual exploitation and abuse

-

Drug and alcohol misuse

-

Mental and sexual health issues

-

Exclusion from school and failing to meet educational milestones

Data from the National Crime Agency36 showed that in 2014/15 across the Lancashire Police Force area, there were:

-

6,733 missing person incidents reported to the police, approx. 18 per day

-

4,941 incidents (73%) related to children,

-

1,660 individual children generated the 4,941 incidents of 'missing from home'

-

approximately 14 missing child incidents per day

-

66% of the missing child incidents are repeat incident; this compares with 52% nationally

-

there are 3 missing incident reports for every missing child

Many of these incidents involve children who are looked after by the local authorities in Lancashire. Children placed in care are disproportionately represented in the missing incident reports compared to children living with parents in a family home. This is due in part to the duty placed with foster carers and residential care staff to report all incidents to the Police. Conversely, it is evidenced in national research that children living with parents in the family home are under-reported, with around two-thirds of incidents never reported to statutory agencies including the police.

In Blackpool, the Police and Local Authority both now have missing from home co-ordinators in place who are responsible for co-ordinating their agency's operational responses to children who are reported as missing. Monthly missing from home panel meetings are attended by Local Authority and Police Early Action, Awaken, Health, Education and Youth Offending Team representatives, together with the missing from home and anti-social behaviour co-ordinators3. During 2015/16 in Blackpool:

-

-

There were an average of 90 non-Looked After Children reported missing one or more times each quarter and 13 three or more times

-

Amongst the Looked After Child population the figures were 33 and 13 respectively.

-

An average of 7 children are reported missing on nine or more occasions each quarter from the overall child population

All agencies, Local Authority, Health, Education, Police, Probation and Voluntary Sector, work together to provide a prompt multi-agency response to CSE to prevent sexual exploitation or to respond to those at risk or experiencing CSE in Blackpool and Lancashire and to secure the prosecution of perpetrators. Key objectives include the identification and protection of those children and young people who are at most risk of being vulnerable, exploited, missing or trafficked and the sharing of information and intelligence in respect of adults who may pose a risk to children.

-

Lancashire Constabulary is committed to preventing child sexual exploitation, helping victims and bringing offenders to justice. It is a crime that can affect any child, anytime, anywhere - regardless of their social or ethnic background

-

The Awaken Project is run jointly by Blackpool Children's Services and the police, based at Bonny Street Police Station. Its aim is to safeguard vulnerable children and young people under the age of 18 who are sexually exploited. It also aims to identify, target and prosecute associated offenders.

-

The Blackpool Safeguarding Children Board is a partnership between the Local Authority, Health, Education, Police, Probation and Voluntary Sector, whose purpose is to ensure that local services provided to children are effective and well-coordinated.

-

Blackpool Council Family Information Service is a free, impartial service offering information, advice and assistance on childcare as well as general information on a wide range of services for children, young people, their families and professionals working with families.

-

Street Safe Lancashire supports children and young people at risk of sexual exploitation and those who are missing from home.

-

Trust House Lancashire offers a safe place and specialist support for those affected by rape and sexual abuse; women, men, children and young people.

-

Lancashire Constabulary's missing people provides facts and information on reporting people missing and on organisations who can help.

Key reports

Office of the Children's Commissioner's Inquiry into child sexual exploitation in gangs and groups: one year on "If it's not better, it's not the end" examines the extent to which the agencies responsible (government agencies and departments, police forces, local authority children's services, Local Safeguarding Children Boards (LSCBs)) have implemented the recommendations made in the Inquiry.

Office of the Children's Commissioner's Inquiry into Child Sexual Exploitation in Gangs and Groups Final Report If only someone had listened. This report outlines the urgent steps needed so that children can be effectively made and kept safe - from decision-making at senior levels to the practitioner working with individual child victims.

2014 Jay report into Child Sexual Exploitation in Rotherham documents Rotherham Borough Council's response to issues around child sexual exploitation.

The Ofsted inspection report to evaluate effectiveness of local authorities' current response to child sexual exploitation: The sexual exploitation of children: it couldn't happen here, could it?, November 2014

The new Joint Targeted Area Inspections (JTAIs) of services for vulnerable children and young people (JTAI) launched in 2016, involving CQC, Ofsted, Her Majesty's Inspectorate of Constabulary (HMIC) and Her Majesty's Inspectorate of Probation (HMIP). All four inspectorates will jointly assess how local authorities, the police, health, probation and youth offending services are working together in an area to identify, support and protect vulnerable children and young people.

The Ofsted report, Time to listen: a joined up response to child sexual exploitation and missing children summarises the findings from the 'deep dive' element of five joint targeted area inspections. The deep dive aspect of the inspection evaluated the experiences of children and young people at risk of, or subject to, child sexual exploitation. It also looked at children missing from home, care or education, given the links between children missing and child sexual exploitation.

Coventry University's Child Sexual Abuse and Exploitation: Understanding Risk and Vulnerability (August 2016) is a rapid evidence assessment of the best evidence for identifying and appraising risk indicators for child sexual abuse and child sexual exploitation.

The Department for Education Child sexual exploitation: support in children’s homes reports on the support provided to children placed in residential care who have experienced, or are at risk of, child sexual exploitation (December 2016)

Key strategies

National guidance (safeguarding children and young people from sexual exploitation) requires agencies to work together to:

-

-

Develop local prevention strategies;

-

Identify those at risk of sexual exploitation

-

Take action to safeguard and promote the welfare of particular children and young people who may be sexually exploited

-

Take action against those intent on abusing and exploiting children and young people in this way

In 2015 the government published its Tackling Child Sexual Exploitation cross-government action plan. It included a commitment to delivering a new system of multi-agency inspections to 'reinforce the need for joint working at all levels and better assess how local agencies are working in a co-ordinated manner to protect children and young people'.

Tackling child sexual exploitation: progress report (February 2017) focuses on progress against the actions set out in Tackling Child Sexual Exploitation, in the context of wider government work developed since March 2015 to tackle child sexual abuse.

The pan-Lancashire Child Sexual Exploitation Multi-Agency Strategy 2015-2018 is the joint Lancashire Constabulary and Lancashire, Blackpool and Blackburn with Darwen Safeguarding Children Boards plan to address CSE.

One of the 3 key priorites for the Blackpool Children and Young People's Plan 2013-2016 is to keep children and young people safe, preventing them entering the care and custody system wherever possible and ensuring there are safe and effective exit routes.

The CSE sub-group of the Children’s Safeguarding Board is working to create a CSE dataset and police data collection systems are being updated. This work will help to establish the extent and nature of CSE within Blackpool and inform future policy development.

The Blackpool Safeguarding Children Board Child Sexual Exploitation and Missing Children Operational Action Plan 2016-18 states the board must:

-

-

provide clear leadership is in place that provides a long term vision and aim in relation to CSE/Missing Children.

-

engage with communities, to raise awareness and understanding of those at risk of CSE and going missing to prevent children and young people from becoming victims.

-

be reassured that they identify and protect children and young people at risk of, or subject to sexual exploitation and/ or going missing to safeguard, support and prevent them from further harm.

-

ensure that there are processes in place to identify and target perpetrators and potential perpetrators of CSE.

-

be informed of the partnership arrangements within its borders and the level of specialist commitment by partnership organisations.

-

be provided with key data from partner agencies to gain greater knowledge and understanding of CSE and missing children in the area.

-

ensure that appropriate learning and development opportunities are in place for supervisors and front line staff regarding CSE.

[] PHE. Child sexual exploitation: How public health can support prevention and intervention. Part 1 (the framework), July 2017. [Accessed 21 August 2017]

[] NSPCC. Child Sexual Exploitation: What is Child Sexual Exploitation, 2017 [Accessed 21 March 2017]

[] CEOP, Threat Assessment of Child Sexual Exploitation and Abuse, Child Exploitation and Online Protection Centre, June 2013.

[] Barnado’s. Be Safe: Helping you protect your child 2017. [Accessed 21 March 2017]

[] European Cyber Crime Centre. The Internet Organised Crime Threat Assessment (iOCTA). 3.3. Child Sexual Exploitation: Overview. 2017.

[] Childline, Online Grooming 2017. [Accessed 21 March 2017]

[] NSPCC, Sexting: Advice for Parents 2017. [Accessed 21 March 2017]

[] Barnado’s, Child sexual exploitation – can you see it? 2017 [Accessed 6 June 2017]

[] Bowyer S, Branigan P and Constable S (NSPCC). Responding to harmful sexual behaviour including peer to peer abuse – an evidence informed framework 2017 [Accessed 6 June 2017]

[] Hackett S, Holmes D and Branigan P (NSPCC), Harmful Sexual Behaviour Framework: An evidence-informed operational framework for children and young people displaying harmful sexual behaviours. 2016 [Accessed 6 June 2017]

[] Radford L, Corral S, Bradley C, Fisher H et al.(NSPCC), Child abuse and neglect in the UK today, 2011 [Accessed 6 June 2017]

[] Hackett S (Research in Practice). Children and Young People with Harmful Sexual Behaviours. March 2014.

] Almond L, Canter D and Salfati CG. Youths who sexually harm: A multivariate model of characteristics. Journal of Sexual Aggression 2006;12(2): 97-114

[] Barnados, Working with children who are victims or at risk of child sexual exploitation, Barnardo’s model of practice, 2017 [Accessed 27th June 2017]

[] Children’s Commissioner, “If only someone had listened” The Office of the Children’s Commissioner’s Inquiry Into Child Sexual Exploitation in Gangs and Groups – Final Report, November 2013 [Accessed 27 June 2017]

[] Children’s Commissioner“I thought I was the only one in the world” The Office of the Children’s Commissioner’s Inquiry Into Child Sexual Exploitation in Gangs and Groups – Interim Report, November 2012. [Accessed 27 June 2017]

[] PHE. Child sexual exploitation: How public health can support prevention and intervention - Literature search to identify the latest international research about effective interventions to prevent child sexual abuse and child sexual exploitation. July 2017 [Accessed 21 August 2017]

[] NSPCC, Child trafficking – what is child trafficking? 2017 [Accessed 21 August 2017]

[] Chung RJ and English A. Commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of adolescents. Current Opinion in Pediatrics 2015;27(4): 427-33

[] Greenbaum J and Crawford-Jakubiak JE. Child sex trafficking and commercial sexual exploitation: Health care needs of victims. Pediatrics 2015;135(3): 566-574

[] Hornor G. Domestic minor sex trafficking: What the PNP (paediatric nurse practitioners) need to know. Journal of Pediatric Healthcare 2015;29(1): 88-94

[] Varma S, Gillespie S, McCracken C et al. Characteristics of child commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking victims presenting for medical care in the United States. Child Abuse and Neglect 2015;44(98-105)

[] Vennema TG, Thornton CP and Corley A. The public health crisis of child sexual abuse in low and middle income countries: an integrative review of the literature. International Journal of Nursing Studies 2015;52(4): 864-881

[] UNICEF. Note on the definition of ‘child trafficking’ March 2017 [Accessed 21 August 2017]

[] McClain NM and Garrity SE. Sex trafficking and the exploitation of adolescents. Journal of Obstetric, Gynaecologic and Neonatal Nursing 2011;40(2): 243-252

[] Barnado’s, Child Trafficking Advocacy – Trafficking Risk Factors 2017 [Accessed 21 August 2017]

[] Fedina L, Williamson C and Perdue T. Risk factors for domestic child sex trafficking in the United States. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 2016. DOI [Accessed 21 August 2017]

[] National Center on Safe Supportive Learning Environments. Human Trafficking in America’s Schools – Risk factors and Indicators2017 [Accessed 21 August 2017]

[] Jay A. Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Exploitation in Rotherham 1997-2013 August 2014 [Accessed 6 September 2017]

[] Klonowski A. Report of the Independent Reviewing Officer in Relation to Child Sexual Exploitation Issues in Rochdale Metropolitan Borough Council During the Period 2006 to 2013 May 2013 [Accessed 6 September 2017]

[] Safer Lancashire, 2015 Pan Lancashire Strategic Assessment, Technical Report: evidence base

[] DfE, Characteristics of Children in Need: 2015 to 2016 (SFR 52.2016)

[] Blackpool Safeguarding Children's Board Annual Report 2016/17

[] Coventry University, Child Sexual Abuse and Exploitation: Understanding Risk and Vulnerability, August 2016

[] DfE, Statutory guidance on children who run away or go missing from home or care, Jan 2014

[] National Crime Agency, UK Missing Persons Data Report 2014/15, May 2016

[] The Children's Society, Still Running 3, Early findings from our third national survey of young runaways, 2011.